Bring Sex & Eros To Buddhism

Talking about healthy sexuality prevents abuse. Also: good sex is good for you.

Thank you for reading Your Wild And Radiant Mind! I’m able to make this work happen through the generosity of free and paid subscribers. If you would like to further support my writing, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. You’ll also gain access to mini-salons, classes, prompts, the archive, and personalized creative advice.

Hi y’all,

This post is about both healthy sexuality and also, sexual abuse and assault. I know that the topic is a hefty one and have included a lot palate cleansers at the end of this newsletter about stuff I love. Nothing explicitly graphic is mentioned in the actual post.

Even so, please consider this a content warning.

✨ Before We Dig In…

If you are asking yourself why you should keep making your art and stories and poems and music while the world is on fire, please join me and Ines Bellina on Thursday, May 8th from 12-12:40pm CST for a mini-salon about the meaning of it all, and the meaning behind it all. Expect existential depth plus goofiness. Sign up and find more details here for the mini-salon.

This is a pay-what-you-can event with $15 as a suggested donation, but we gratefully accept all amounts. Paid subscribers get in for free can send us a question on the topic.

Sign up for the mini-salon “Why Even Make This: Finding Spiritual & Practical Meaning to The Creative Process.” for 5/8

On Tuesday, June 3rd from 7-8:15pm CST, I’ll be teaching a creative writing class, “The Answer Is Already Here: Make Your Own Writing Oracle.” You'll learn how to use the oracles of collage and bibliomancy to gather inspiration for new ideas, get "unstuck” on creative projects, build more meaningful patterns in your work, and ask yourself better questions. Sign-up and find more details here.

Details about both events are in the sign-up forms. Paid subscribers receive free access to both the mini-salon and the class, including recordings for both.

Sign up for the class, “The Answer Is Already Here: Make Your Own Writing Oracle” for 6/3

Ok! Onto the actual post…

Lately, I’ve been thinking of how we ignore and normalize male suffering, and how ignoring men’s suffering leads to sexual violence against women.

When I was a college student, I was raped by a male student in a summer creative writing program. The man who raped me was an MFA student, a few years older than me, and an alcoholic who, during the program, passed out underneath bridges, walked home barefoot across broken glass cutting up his feet, and drank heavily with a male professor at bars.

Let’s call this man Caleb.

Two nights before I was raped, two male professors and a few male students moved a chest of drawers in front of Caleb’s bedroom door so he wouldn’t leave. Caleb screamed and pounded on the door in a drunken rage. The men laugh at his behavior. Likely, I also laughed. At the time, I also thought he had just gotten out of hand. I hadn’t been around raging alcoholics. I didn’t understand that Caleb was not well.

The older people—the people in charge—seemed to think he was harmless, so I also, thought he was harmless.

One evening, near the end the program, I had two beers and a hot toddy, over the course of a meal and a few hours. Usually this amount of alcohol would leave me tipsy but not drunk. I wanted to be careful because I was finishing a course of antibiotics, and worried that the alcohol might lose its effectiveness.

Instead, I experienced overwhelming vertigo, dizziness, and disorientation as a result of mixing the antibiotics with alcohol.

I was sitting alone on the beach with Caleb. He offered to walk me home, and I accepted his offer. As I left, he held my hand to steady me because I was so dizzy. Two men my age, who I considered friends at the time, saw me leaving the beach holding hands with Caleb and believed this was an act of sexual consent. They would later not believe that I was raped.

I was so sick from medication and alcohol that on the walk home I stumbled and fell more than once. I could hardly walk. The palms of my hands stung for days. My knees turned black and blue. I was scared and crying. Instead of walking me to my dorm room, Caleb took me to his.

I won’t go into detail what happened next.

The next morning, in shock, I took a back, went to breakfast, and tried to act normal. It took me several hours to come to terms with the fact that I had been raped.

What angered me then, what still angers me, was the way that the faculty—the people in charge—abdicated responsibility for the behavior of the student, which was full of red flags. He was not well, and his illness was a safety issue. Their acceptance of his behavior normalized his behavior.

A Lover Is A Friendship Swirling With Eros

When I got back home to where I attended to college, my girlfriend at the time broke up with me. I stopped going out. I stopped making friends. I kept to myself. I had gone to the summer program to write poetry, and I quit writing poetry. It went on like this for a while. I didn’t experience PTSD, but I felt on-and-off sad and disconnected from life.

In the following years, one of the things the things that healed my relationship to myself was having satisfying, healthy sexual relationships with men. I slept with a couple of men who fit the category of both friend and lovers. It felt good not to have to draw a tight circle around one thing.

One of these men was a friend I’d known since high school. We’d always clicked, but for years, preceding the rape I’d experienced, I had the pattern of becoming romantically attached to people who were either emotionally volatile or emotionally unavailable. Jake was one of the first times I had a physical relationship with someone who was neither.

I could feel him admire me and support me and love me without being jealous, possessive, or judgmental. We were both in open but committed relationships at the time with other people, and we felt secure and happy with the limited time we had together. There was never any doubt in either of our minds that our friendship would continue after we quit sleeping together. I could write an entire post that is a love letter to him and our friendship, and how much this person continues to mean to me, and how supportive and steady he has been in my life. He continues to be a kind of platonic lover, in the sense that I have never stopped deeply loving him or being in awe of him.

Being lovers with Jake didn’t singularly cure me of my attraction to people who weren’t good to me. But I still think this relationship became a kind of touchstone, a kind of model. What does it be like to feel the charge of attraction, the suspense, the excitement, with someone who also feels safe? Could a sense of the erotic charge also feel secure? Could security even heighten a sense of attraction or arousal because it allows us to be vulnerable, tender, and not judged?

Experiencing this relationship with a friend who was also a lover, planted a seed of renewal. I remember when he got married, a mutual friend called me up.

“I always hoped you would marry Jake,” she said.

My heart felt a weird pang when she said it.

It dawned on me that maybe we should all feel like our lovers are our friends. Maybe our lovers and romantic partners should support us and respect and be there for us in the same way that a friend is. Maybe that’s what a true lover really is: a friendship swirling with Eros. And maybe that’s what sex can be—a respectful, nonjudgmental, deep sharing of pleasure, and accepting that intense pleasure is often tied to our pain and our deepest longings.

His marriage woke me up to the fact that I was not attracted to men who were nice to me. I needed to change. It was as though his marriage rewired my brain and body. Within a couple of months, I left the unhealthy relationship that I was in. I met my husband.

Sexuality and Eros isn’t just a setting for healing, it’s a place of growth and renewal and the discomfort that accompanies transformation.

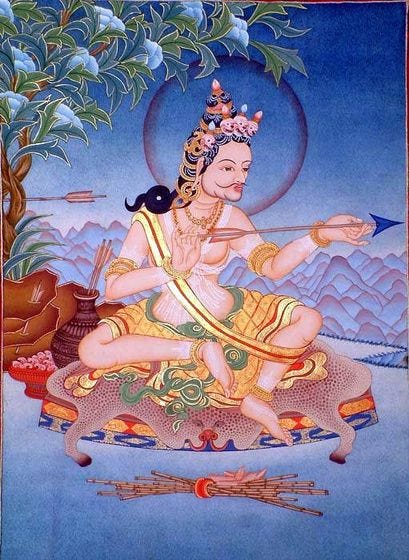

Vajrayana Buddhism is filled with stories of transformation through sexuality. Saraha, a famous yogi, watched a woman making arrows in the marketplace. While watching, he suddenly realized that she was a highly realized yogini. The arrow-maker took on Saraha as her partner and disciple, and she became his guru1.

Those terms now—guru, disciple—are so often used in ways that feel loaded and gross culty in Western culture. But looking at the story, what seems to have happened here is that a man looked at an ordinary woman and realized that she wasn’t so ordinary. That maybe he had something to learn from her. Eros punctured the veils of ignorance in Saraha, which included the veils of gender, education, and caste.

Unless you vividly remember your past lives or have access to a time-travel machine, we can’t exactly say what their relationship meant in medieval India. The dynamics of sexuality, gender, and power are constantly changing within our social context. But these stories have survived for a long time because they continue to instruct us on how we can learn from others across difference. That includes our romantic and sexual partners.

It’s feels serendipitous, interplay of cultures that Saraha’s female guru and partner was an arrow-maker, and that in ancient Mediterranean Greek culture, Eros shoots our hearts with arrows when we experience attraction. Eros had something to teach Saraha and Eros continues to has something to teach us.

We learn about our own awakened minds by being present and curious with those we’re physically intimate with, because a powerful energy is being shared and exchanged. If you are married or partnered or have a lover—or even if you have respectful sex with someone you don’t know very—sex subtly changes you through the through an exchange of vital energy. If you love someone deeply, even more so.

Sex makes us feels good. It doesn’t have to be all spiritual or holy or sacrosanct to understand the very simple idea that relationships and sexuality are transformative. Sex is not the same as love. But still, sex can put us back inside ourselves.

What Feels Good Restores Us

I thought of all this last year, in early 2024, when I read yet another abuse case in Vajrayana Buddhist world. The case was not an example of “sexual misconduct,” nor it does fall into that more nebulous category, “a misuse of sexuality.” The testimony of the victims details extreme violence, rape, and emotional abuse in a cult-like environment.

There are so many of these abuse cases, it’s sickening. And it feels relentless. If you are reading this and you’re not a Buddhist, I don’t think it’s exaggerating to say that there are parallels in the Buddhist world to the Catholic church, both with children and with women. This seems to be the case across all sects of Buddhism, but particularly in Vajrayana. If I wasn’t certain that the tradition was also full of amazing, fundamentally decent people I would have left a while ago.

I talked to a male friend and practitioner who was also upset by the recent case. We both felt angry and disgusted. Most men don’t rape women. What are the conditions in Vajrayana that creates environments for this kind of abuse? The usual suspects floated up—toxic masculinity, misogyny, rape culture, the removal of tulkus2 as young boys away from their mothers at very early ages, Orientalist idealization and dehumanization of Tibetan teachers, unhealthy secrecy around certain practices, and the distorted relationships between senior students, Lamas, and novice students.

After our conversation, I thought of the way the man who raped me was hurting, and how the older people—the people in charge—could have chosen to acknowledge how he was hurting, and done something. But because they laughed off Caleb’s suffering. He was not sent home. No one watched him or me with a protective, vigilant, caring eye.

This dynamic felt similar to the one so many of these sanghas where abuse occurs. A group of people who should know better enable a man who is obviously experiencing some kind of serious pathology. He gets by with it not just because he’s in a position of power, but because he is a man in a position of power.

The expectation of masculine stoicism—that men aren’t allowed to express pain in healthy ways—is utterly toxic when it is combined with projections of spiritual power. Being a realized teacher really doesn’t make you less of an asshole. Glimpsing the absolute nature of reality is not always contingent on being an emotionally mature, well-adjusted person.

Over and over again, patterns of male sexual violence are excused and enabled in spiritual communities. Because this pattern mirrors what is enabled outside of spiritual communities.

When Caleb was locked in his room, the men laughed, because boys will be boys, right? Imagine a woman screaming at the top of her lungs, throwing herself into the door of her room, and someone not calling an ambulance or the police to take her to a psych ward or rehab clinic to dry out.

No one else offered to walk me home that night, including the female faculty. No one else asked me how I was feeling when I sat alone, dizzy and disoriented. Why didn’t the elders in any of these communities, mine and in these sanghas, do something? I’m in my forties now, and I knew I didn’t want to be like them. I feel protective of young people—I’m a parent of two young children and I teach creative writing to college students. I wanted to do something.

I was pissed.

Usually when I’m pissed, I want to write something about it.

So I sat down to do it.

Like any responsible writer, I looked to see what had already been written. I discovered a wealth of work and resources on the subject of abuse in Buddhism. The work is brave, extensive, and groundbreaking. I realized that I didn’t have much new to add to the conversation, so I took a step back, and thought about how I might contribute.

It felt to me that the most helpful thing I could offer as a writer and practitioner was a kind of secondary, auxiliary response: A reclamatory call for the power of sexuality, particularly the experience of woman’s sexuality and gendered experience. The thing that struck me about the important conversations that were happening that they were not actually about sex—because sexual abuse isn’t really about sex, it’s about power. It’s about a someone feeling small and powerless who exerts control over someone who is smaller and weaker as way to feel more powerful.

This is where healthy sexuality can be so instructive. Regardless of if we’ve been abused or not, sexuality can serve us as profound energy that makes us feel whole, connected, and alive. This wound of abuse in the Buddhist world isn’t isolated to Buddhism. If it’s in the world, then it’s also going to also be in the Buddhist world. To heal that wound, an acknowledgement and discourse around healthy sexuality—its complexity, its pain, its joy, its bewilderment—needs to take place.

We need to know and remember aloud what feels good, to be able to help others discern between the ordinary confusion that so often happens in respectful, consensual sexual relationships, and the trauma of sexual abuse. This talking aloud guides young people in their own experiences of attraction. If you don’t know what feels good in sexual relationships, it’s easier to believe that feeling awful is normal.

Not only that, sexuality and partnership are part of the human experience. As lay-Buddhist practitioners, we can take our ordinary, joyful experiences from daily life, like sexuality, and use those as methods to understanding our naturally awakened mind.3

So rather than contributing a response about sexual abuse in Buddhism, I started writing about sexuality, gender, Eros, and dharma in their consensual and complex manifestations. It was the reason why I started this Substack in February 2024. The very first post that I published on accessibility, gender, and sexuality: “What Strip Clubs Can Teach Us About Dharma,” will be out in the summer print edition of Tricycle under the title, “The Price of Dharma.”

I truly hope this piece benefits others.

You can also find more on sex, desire, Eros, and partnership in the paid archive:

“Falling In Love Teaches Us How to Meditate: Love at first sight and Mahamudra”

“Unlocking Bliss: Exploring the Erotic in Vajrayana Buddhism and Beyond”

Keeping comments to paid subscribers on this one folks, because being a woman on the internet while writing about sex and religion is completely safe, lol ✌🏼

Stuff I’ve Loved:

Speaking of good men who think women are cool, John Berger, the art critic who coined the phrase “the male gaze,” had some remarkable things to say about tenderness, pain, and non-judgment in this amazing interview.

I went to L.A. in late March and saw the María Magdalena Campos Pons exhibit at the Getty twice because I love her work so much and how it deals with so much: plants and their cycles of migration, decay, and renewal, Santeria, multi-racial ancestry, exile, homeland, and dissent.

The Buddha In The Attic by Julie Otsuka is a novel narrated from the collective point-of-view of “picture brides” from Japan to the U.S., and follows them into the internment of Japanese-Americans to concentration camps in World War II. This novel has an elegant power and is one of the most formally innovative works I’ve ever read. It made me cry.

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar, is a book I avoided because tbh, novels by poets often don’t have a sense of humor and I demand a sense of humor if I’m committing to three-hundred pages. But Akbar’s novel is so daring and lovely and also, I stand corrected: poets can be funny novelists.

I was tickled pink to watch comic Andi Marie Tillman talk to her mother about death and the natural gothness of Appalachian women. I felt seen.

In case you missed it…

Writer

interviewed me for Be Where You Are, a fantastic, uplifting publication on writing, motherhood, aging, mindfulness, and other things. I talked about how devotion changes our perception, writing in the cracks of time, first drafts, and practicing Dzogchen. You can read that interview here.In the last couple of months I’ve written about dance, colonial legacies, and the dakini, bringing the pleasures of meditation to my writing life, and strength as generosity.

I was saddened to hear that the writer Jesse Kornbluth passed away in April. It was humbling to see excerpts my 2015 The New York Times book review for his novel, Married Sex, as part of his obituary. I loved reading and review Korbluth’s novel. There’s so much toxic masculinity in literature that it feels deeply refreshing (and kind of rare) to read a depiction of well-adjusted, healthy male sexuality. May he rest in bliss and peace and delight.

Funny how the arrow-maker, as Saraha’s guru, was the more highly realized practitioner but her name has been lost to time. We only know her as “the arrow-maker.” When will men realize that they are hurting themselves when they leave out women’s names from the story?

Reincarnated Lamas.

An excellent resource on the subject of sex and meditation is Dr. Nida Chenagtsang’s book The Yoga of Bliss. Dr. Chenagtsang is a physician of traditional Tibetan medicine and a Ngapa, a vow-holding, non-monastic Buddhist practitioner.

Thank you for the courageous and thoughtful post.

I‘m really sorry you had to go through that.

There’s so much to explore here. In terms of practice I enjoyed Julie Henderson‘s The Lover Within. Have you come across that?